17. Alexander Theroux — The Lollipop Trollops & Other Poems

17. Alexander Theroux — The Lollipop Trollops & Other Poems

My pledge this year is to read more contemporary poetry. I used to review poetry in online workshops, and the nimiety of lowercase e.e. cummings imitations left me exceedingly depressed. I can’t write poems for toffee (and toffee sellers only accept sestinas as payment) but I believe modern poets should acquaint themselves with as many poetic forms as possible, unafraid to box themselves into the metrical requirements of a sonnet or an englyn. When I tried poems I took arbitrary line breaks based on hunches—I needed the constraints of a good form to see me right. But I didn’t have the patience. Anyway, this collection demonstrates an excellent range of rhyming poems (in the 90s!) and free verse dalliances, tackling the trivial, the peevish and the profound. The man’s a damn fine poet. The writer is an essayist and author of Laura Warholic: The Sexual Intellectual.

18. Alasdair Gray — Collected Verse

18. Alasdair Gray — Collected Verse

Alasdair Gray: artist, muralist, doodler, novelist, short story writer, playwright, teacher, historian, translator . . . AND poet? Is there anything this fat asthmatic Glasgow pedestrian can’t do? As a poet he’s no Hugh MacDiarmid but this collection shows he’s no slouch either. The most impressive poems here are his gloomier, earlier poems about voids and loneliness, they ring the truest of all. Some of the later work is eccentric and doesn’t merit rereading . . . ESPECIALLY the Latin translations which are EXTREMELY DULL! My, I’m abusing the caps lock tonight, for sure. For the completists, this volume contains his separate collections Old Negatives and Sixteen Occasional Poems, as well as all the bits and pieces scattered in art galleries and anthologies throughout his life. Two Ravens Press, based on the isle of Uist, have done a stellar job designing this little hardcover edition. On an unrelated note, this Glasgow band Veronica Falls are fucking brilliant. And goodnight.

19. Kurt Vonnegut — Fates Worse Than Death

19. Kurt Vonnegut — Fates Worse Than Death

This is Vonnegut’s last in the trio of “autobiographical collages,” which is a canny way of presenting various nonfiction materials without having to impose a structure on the book. This is the most shambolic of the three—firstly, Fates Worse Than Death is divided into conventional chapters, so the reader has no contents table to peruse the various speeches Kurt reproduces here from recent public speaking events. And the book is mostly reproduced public speeches, most of which are entertaining and erudite in his typical style, but some of which become tiresome. Imagine sitting through several hours of Vonnegut lecturing. That effect is created here. On the positive side, although he repeats facts about his life from previous books ad nauseam (did you know he worked for General Electric? and was at Dresden?), the commentary on his family is illuminating among the shrubbery of opinion. Not to say the revelation he tried to commit suicide in the 1980s, which is barely discussed and leaves me craving more detail. So yes, absolutely for diehards only. Those wishing to dip a toe into his nonfiction try Palm Sunday.

Performed at the Edinburgh Book Festival in 2011, with Alasdair Gray as Old Nick, poet Aonghas MacNeacail as God, Will Self as John Fleck, and A.L. Kennedy as May. I missed the performance in August because I am stupid. Also onstage were folk like Liz Lochhead, Ian Rankin and Alan Bissett, so I say again: I am stupid. Reading the play on my lonesome was no consolation for this missed opportunity, although I take some pleasure knowing it isn’t very good. A contemporary version of Goethe’s Faust written in comedic verse? Why does that sound like flogging a horse that decomposed years ago? (Two Ravens Press aren’t to blame: this edition is beautifully designed). The world doesn’t need more modern versions of Faust. We could spend an afternoon naming all the films and books and songs about selling one’s soul to the devil. And we’d fall asleep.

21. Kurt Vonnegut — God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian

21. Kurt Vonnegut — God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian

For an extremely short period of time in the late nineties, Kurt was “Reporter on the Afterlife” for the WNYC radio station in, presumably, NYC—hence the station’s name. (Columbo in the house!) This extremely short book compiles his ninety-second radio spots, where he met such figures as Dr. Mary D. Ainsworth, Adolf Hitler, Sir Isaac Newton and Isaac Asimov. Following Timequake, these little pieces were, more or less, what Kurt did towards the end of his life—little paragraphs of philosophical apothegms, autobiographical reflection, and consistently sharp social comment, all written with a cutting wit and humanist bent. If there were an online repository for Kurt’s taped interviews, speeches, appearances, etc (on his website would help) these sorts of collections wouldn’t need to exist. But I’m glad it does. And, on this fortunate occasion, you can listen to the original broadcasts here.

22. Kurt Vonnegut — A Man Without a Country

22. Kurt Vonnegut — A Man Without a Country

Something of a misnomer, this title: “A Memoir of Life in George W. Bush’s America.” Hmm. No. In fact, Kurt’s final book is another collage of pieces taken from public speeches, and various articles commissioned for the publication In These Times. Michael Silverblatt described this book as a “response to a plea”—that plea coming from the editors of Seven Stories Press, who tickled Vonnegut into writing little chunks again. Any fresh writing from an eighty-three-year-old man is hard to come by, and Kurt recycles passages from previous books, most notably Dr. Kevorkian. But who cares? This collection is deftly edited to give Kurt’s words real power through brevity, and a cadence is established throughout, building to a moving climax. Not bad for a man without a country. The excrement has truly hit the air conditioner. (P.S. Portions of this appear in this excellent speech).

23. Geoffrey Hill — Mercian Hymns

23. Geoffrey Hill — Mercian Hymns

These poems put me in mind of PJ Harvey’s latest, Let England Shake. All soil and toil, fantastic gloom. I nabbed this collection from my girlfriend who knows how to read poems. Ask her, she’s nicer than me, and a talented playwright. Or perhaps you can form your own opinion? Here’s stanza III, part XXII to consider: “Then, in the earthly shelter, warmed by a blue-glassed storm-lantern, I huddled with stories of dragon-tailed airships and warriors who took wing immortal as phantoms.” That sort of thing. Very English!

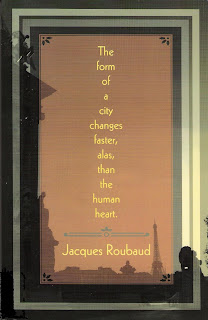

24. Jacques Roubaud — The Form of a City Changes Faster, Alas, Than the Human Heart

Jacques Roubaud’s most recent collection of poetry explores the streets of Paris, the idle hours spent ambling around this distinctive city, with an emphasis on place names over scenery. Roubaud responds to work from Queneau (the first cycle is a take on his collection Les pauvres gens), Verlaine, Rimbaud and esoteric historical figures. From meditations on death to playful Oulipo antics, wilful obscurity and silly throwaways, this is about as deliciously uplifting a collection as a poor deprived Scot could expect to read. I have a sore throat and stuffed nose right now (a detail you all needed to know), so this is the perfect medicine (that and Glycerine). Read Roubaud, read Roubaud!

Jacques Roubaud’s most recent collection of poetry explores the streets of Paris, the idle hours spent ambling around this distinctive city, with an emphasis on place names over scenery. Roubaud responds to work from Queneau (the first cycle is a take on his collection Les pauvres gens), Verlaine, Rimbaud and esoteric historical figures. From meditations on death to playful Oulipo antics, wilful obscurity and silly throwaways, this is about as deliciously uplifting a collection as a poor deprived Scot could expect to read. I have a sore throat and stuffed nose right now (a detail you all needed to know), so this is the perfect medicine (that and Glycerine). Read Roubaud, read Roubaud!

25. Émile Zola — The Masterpiece

You have this friend, a writer. He’s written this terrible bildungsroman about his tedious student exploits, I Want Vagina. You tell him tactfully that a 900-page, unspellchecked homage to sexual frustration doesn’t fly in the marketplace. Your friend scurries off and signs up for a Creative Writing MA at Dorset Polytechnic, taught by Vernon D. Burns. He returns, a few months later, with a new 900-page spellchecked homage to sexual frustration, I Want to Squeeze Bosoms. You arrange for him to lose his virginity so his art might progress by dialling a friendly helpline for that purpose (Callgirlz2nite). He returns a year later with a new epic, I Love Sleeping With Whores. His prose abounds in loving descriptions of thighs and calves and thighs, but lacks a greater purpose. A novel needs something more than loving exudations of prozzies to be successful (a few classics notwithstanding). Your friend trundles off. He rents a box room and starts his masterpiece, A Novel With Substance, Truth & Power. You tell him to rethink the title, but he tells you to shut up, he knows what he’s doing. So: skip twelve years, past the four breakdowns, nine marriages, one suicide attempt, to the final draft of his masterpiece. You sit down to read this dense marsh of unreadable prose, despairing at each spontaneous MUMMY that looms from the text (often LOVE ME MUMMY), and watch a sitcom instead. The message? All artists are fucked up. Some are—as they say in the US army—fucked up beyond all recognition.

Uplifting passage, spoken by the character based on Zola:

Uplifting passage, spoken by the character based on Zola:

“From the moment I start a new novel, life’s just one endless torture. The first few chapters may go fairly well and I may feel there’s still a chance to prove my worth, but that feeling soon disappears and every day I feel less and less satisfied. I begin to say the book’s no good, far inferior to my earlier ones, until I’ve wrung torture out of every page, every sentence, every word, and the very commas begin to look excruciatingly ugly. Then, when it’s finished, what a relief! Not the blissful delight of the gentleman who goes into ecstasies over his own production, but the resentful relief of a porter dropping a burden that’s nearly broken his back . . . Then it starts all over again, and it’ll go on starting all over again till it grinds the life out of me, and I shall end my days furious with myself for lacking talent, for not leaving behind a more finished work, a bigger pile of books, and lie on my death-bed filled with awful doubts about the task I’ve done, wondering whether it was as it ought to have been, whether I ought not to have done this or that, expressing my last dying breath the wish that I might do it all over again!” (p259-60)

26. Michel Houellebecq — Whatever

26. Michel Houellebecq — Whatever

You have this friend who works in IT. He is rendered sick at the torturous formality and bureaucratic inevitability of existence, and slaps you on the face twice before bursting into tears. You phone his friend Tisserand who is unbearably ugly and hits on you twice, for help. You say: “You are so hideous, no woman would go anywhere near you, you disgusting pustule of a man.” Tisserand breaks down in tears but comes back with a brutal salvo: “You women are callous stiff planks who’re only out for yourselves!” Or words to that effect. But your friend who works in IT is looking extremely peaky. He, naturally, has no problem getting laid (despite his own physical shortcomings, i.e. he looks like Michel Houellebecq) but he does seem to be coming down with a bad case of lifesickness. Clearly, traveling around France training people in IT packages is no sound basis for a life. So your friend writes strange animal stories then checks himself into a psych ward. You don’t hear from him for a while, for he is a gone man. A long gone man. (P.S. Worst cover and mistranslated title ever. Original: Extension du domaine de la lutte).

Favourite passage:

“Writing brings scant relief. It retraces, it delimits. It lends a touch of coherence, the idea of a kind of realism. One stumbles around in a cruel fog, but there is the odd pointer. Chaos is no more than a few feet away. A meagre victory, in truth. What a contrast with the absolute, miraculous power of reading! An entire life spent reading would have fulfilled my every desire; I already knew that at the age of seven. The texture of the world is painful, inadequate; unalterable, or so it seems to me. Really, I believe that an entire life spent reading would have suited me best. Such a life has not been granted me.” (p12)

27. Marie Darrieussecq — Pig Tales

27. Marie Darrieussecq — Pig Tales

You have this friend, she’s been out of work for months. Then she gets this gig at a perfume counter, which also involves being a prostitute. She is routinely abused by her “clients” who use her for increasingly perverse sexual practices. She is also, at that time, transforming into a sow. You keep calling to meet for a coffee, but all you get is the answer machine, oinking and grunting her absence. You hear she’s taken up with a politician who sweeps her into the dark sexual underbelly of Paris’s powerful elite, where her fluctuating pigginess proves popular with the higher-ups she lets abuse her rectally. You can forget trying to reach her now. She’s leading a new life with her six teats and wolf boyfriend, she has no time for YOU. It’s frustrating when friends fall away. (This is a delightfully surreal tale with no paragraph breaks).

28. Denis Diderot — Rameau’s Nephew and First Satire

Some editions lump this with D’Alembert’s Dream, others with “other works”—helpful!—but this Oxford Classics edition includes First Satire (some eleven pages). As the one-star rating makes plain, me no likey. Rameau’s Nephew is a rambling conversation between ‘ME’ and ‘HIM’ that feels like an indulgence, written very much for Diderot’s cultural circle, and a very dry run for Jacques the Fatalist. The bantering leans towards the philosophical, and far from being a philistine, I don’t read philosophical tracts because I hate them. The First Satire is equally irrelevant to today’s reader, punctuated with obscure references to figures of the time, copious explanatory notes and flat humour. More to the point, there’s no Diderot magic here, not in the slightest.

29. Jeanne Hyvard — Mother Death

29. Jeanne Hyvard — Mother Death

A raging feminist splurge. 110 pages of staccato attack weapons. Sentences like nunchucks in the knackers. A Lucy Ellmann heroine letting rip after her third divorce and fourth Martini. A full-scale warhead launched against the prevailing male discourse. A repetitive, plotless, placeless, timeless anti-novel. A French theory piece in league with Deleuze or Derrida (men men men). Passages like this: “What do they say? What do they want? For us to have orgasms like them? What do they want? For us to be satisfied with being able to say: she belongs to me? They want our desire to come to an end so they can be more secure in knowing no one else will come along after them. So they make things up. They speak in our place. They teach us the discourses we recite to please them. They think they’re able to converse with us. They talk to their shadows. Because the sea’s voracious mouth is never satisfied. The more they make love to us. The more they fill us. The more they empty us. The more they make love to us. The more desire we have. The more we become the world. The freer we are.” No longer in print. Phew.

30. Brian McCabe — Selected Stories

30. Brian McCabe — Selected Stories

This gentleman was the first writer I met and, since I am gifted at first impressions, I slid two 30-page manuscripts into his office folder before I even spoke to him. The first was an excerpt from a 900-page paean to sexual frustration, parodied earlier as I Want Vaginas. The second was a novel about ending up like your father. Despite their incredible ugliness, he kindly encouraged me to keep writing with no weariness or beeriness in his voice. Later, I took part in his lovely evening workshops where I had the great good fortune to meet my current partner of some five years, and to make people chortle at some sub-Flann O’Brien whimsy I had farted onto my sister’s old PC the night before. All in all, I can safely say Brian McCabe is a top bloke and a brilliant teacher.

And what a writer! Why did I wait five years to read his work? His stories are playful, hilarious, darkly realistic and endlessly ponderable. The story ‘Interference’ about a child who invents a Martian language to deal with his mother’s suicide attempt took my breath away. Written in a perfect early adolescent tone, with an Ali Smith-like flair for language and wit, the story’s devastating core creeps up on the reader like a really good rapist. ‘Anima’ and ‘Say Something’ are equal favourites: the latter a drunken rant from an academic’s wife, with her uninterrupted monologue speaking for the silent man. Other tales deal with life in bleak Scottish towns, among the best ‘The Hunter of Dryburn’ and ‘Strange Passenger,’ the longest piece here, and a great exploration of kids who leave their parents’ social class. Read this man. He’s bloody nice.

31. Georges Bataille — Story of the Eye

31. Georges Bataille — Story of the Eye

The last orgy I attended was in Dundee. I turned up two minutes late, improperly dressed (my gimp mask hadn’t been drycleaned in time), and offended the host by complimenting him on his lovely breasts, and even more cracking vagina. I was told to gently lube the testicles of a history teacher for the first romp—clearly the host was furious with me, as the history teacher was my own father—then invited over for a little frottage against the pelvis of a divorced Cher impersonator. She sang ‘Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves’ to the slow rocking of her climax. What an embarrassing night!

This novella is nothing like that embarrassing night, except the sex is almost as degenerate. No physical descriptions of the sexers are included in the text, so the reader is free to imagine two nubile French handsomes instead of acne-ridden shut-ins (a whole new level of perverse) doing their evil deeds. The writer’s postscript explains the use of eggs and eyes in erotic situations, as some psychoneurotic method of dealing with seeing his blind father struggling to wet himself as a child. If I saw that in my youth, no doubt this is exactly the book I would write. This edition contains an extremely boring essay by Susan Sontag (as long as the novella itself) and a typically inscrutable one from Roland Barthes. Skip those and make up your own theories of perversity (with a partner!)

32. Nicholson Baker — A Box of Matches

32. Nicholson Baker — A Box of Matches

If you turned up at your agent’s office, caught his attention long enough to pitch a new novel idea, and told him the novel would be structured around a box of matches, with each match unleashing a series of domestic anecdotes told by a very boring and precise man, your agent might throw a plant at your head. Nicholson’s agent, however, simply said: “Sounds great, can you have it by February?” Oh, agents. Oh, Nicholson. Oh, mass of unpublished unloved unwanted writers. Oh dear. Anyway, this is another short unoffensive interesting book from Nicholson. But you have to ask yourself, with books like Checkpoint and Vox and so on, where lieth the substance with Baker? These are great books but Baker prances about the place like a colossus of literature, and I think, why why why? He does have the greatest beard in literary history. Counts for a lot.

You actually read 48 books in a month? Impressive, mate. I take it you were doing your best "Johnny 5" impression?

ReplyDeleteI don't know where you got 48 from, but no. I read 32 books this month. Some of them were poetry/novellas, so not as time-consuming. Johnny 5? No. I've heard of Johnny Bravo!

ReplyDeleteI have returned from the sink pit of broken links to offer you this. Your link to the WNYC archive recording of Kurt Vonnegut's 1998 radio broadcast is not to be found where you have pointed. Try it out yourself. Here is the actual link, last time I checked:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.wnyc.org/blogs/wnyc-news-blog/2011/aug/05/kurt-vonnegut-reporter-on-the-afterlife/

cheers

Thanks! I appreciate that, they're great little spots.

ReplyDelete